Josh Watched #15: November 2021

Hi! Sorry I’ve been a little quiet, but look, what do you think of adaptations? Are you into them? Skeptical of them? Does it depend how fondly you feel toward the original IP?

Some people I know refuse to see a movie that adapts a book they love, fearing the images they’ve been carrying around in their heads will smash against the flick’s images like a ship against rocks. For our purposes this month we’re talking mainly about movies adapted from books, but lots of stuff can be adapted: a book or a graphic novel into a movie, a movie into a play or a musical, a play or an opera into a cartoon, a life-form into a life-form more suited to its environment — that’s evolution, baby. A friend of mine in Hollywood is working on a video game adaptation I’m dying to see; its recent cast announcement made the internet say Mamma mia! And the Oscars, recall, have separate awards for original and adapted scripts, since the demands of writing a story fresh differ from those of transmuting one format into another.

So, like, I know that a sharp young reader such as yourself knows what an adaptation is, but let’s keep going with the concept for a couple more sentences. I’ve got adaptations on the brain.

Partly that’s because, as you’ll know if you’re a regular reader of Josh Watched (thanks!), I’ve been adapting myself for the last two years in general, and the last two and a half months in specific. At summer’s end I packed my most cosmopolitan T-shirts to make like a gap-year postgrad and rediscover myself in Europe. Turns out I was one of those life-forms badly suited to its environment; as a friend put it, I needed to repot myself in new soil. Plus, I’d been living in a certain city for far too long, and as with any relationship past its expiration date, I was itching to find out who I was outside it. This is the longest stretch of time I’ve ever spent abroad, and the stretch keeps on stretching. (With a nod to The French Dispatch, the new Wes Anderson flick you’ve maybe seen by now, this month of Josh Watched is my own French dispatch. One reason the edition took a while is it’s hard to find a laptop-friendly café in Paris.)

And partly I have adaptations on the brain because I’ve seen eight of them recently. Two of those (Metropolis, Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance) are around a century old; three (The Odd Couple, Singin’ in the Rain, Heartburn) are in relative middle age or the early elderly years; and three (Dune, The Green Knight, The French Dispatch) are brand-spankin’ new. Some of my friends are confused by how much time I spend in movie theaters when I travel, but the pleasures of seeing flicks abroad are manifold. For one thing, I’m always interested in other countries’ various infrastructures (“How does X work here?”), including theaters both filmic and dramatic.

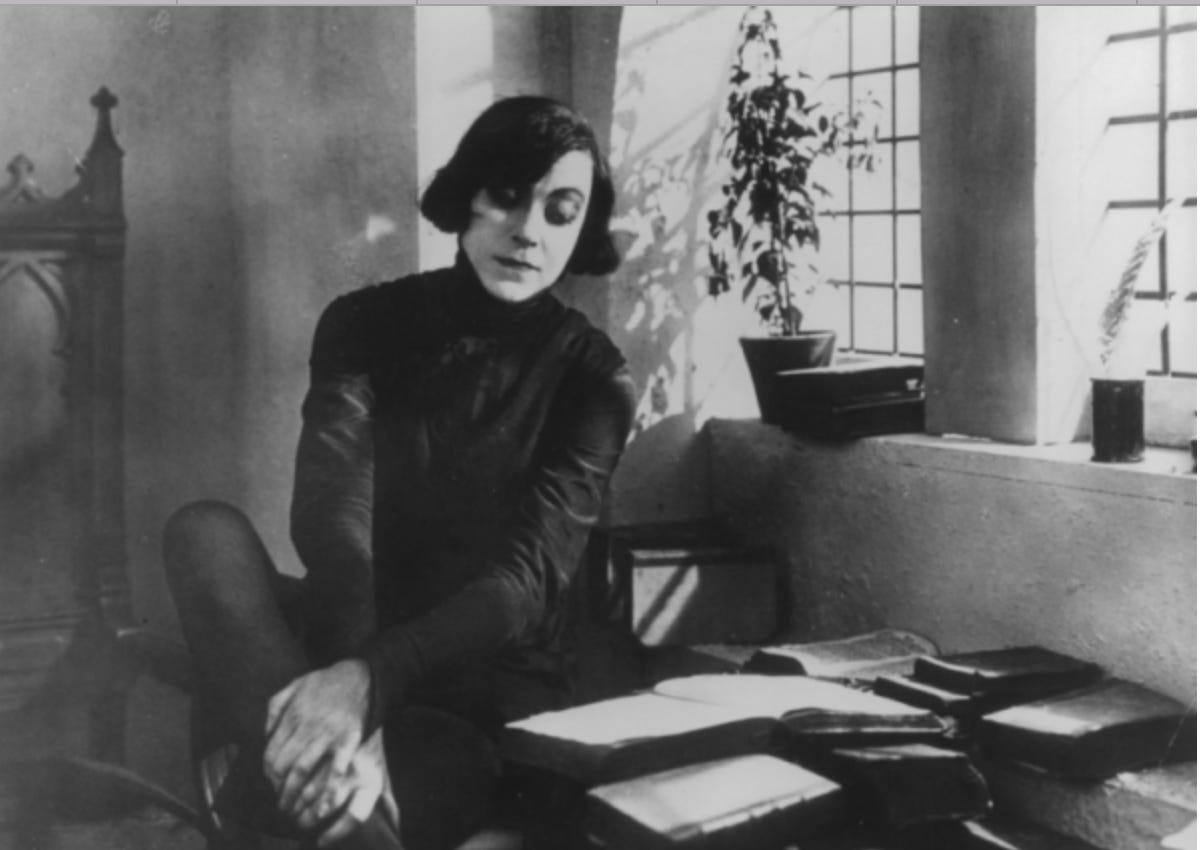

For another, I love film history, and seeing flicks in countries whose national cinemas have rich histories (Germany and France, say) is a treat. To offer one example, the Hamlet adaptation I mentioned a second ago, and will come back to a second from now, is from 1921 and stars Asta Nielsen, a Danish actress who was one of the first German movie stars. I’d never heard of her until I went to the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin a few weeks ago, where there was an exhibit on early German film history. As I learned, she’s less known in the U.S. because her performances were too risqué for the States, as so many things are. A few days after I visited the film archive, lo and behold, one of Nielsen’s best flicks was screening at a Berlin repertory theater, and I bought a ticket and was entranced. (By the way, besides starring in Hamlet, Asta Nielsen also produced it. She founded her own studio in the 1920s, and once she got famous her nickname was The Asta. Having a cool pop-culture nickname is so cool.)

OK, this newsletter is always in danger of disappearing down a rabbit hole or three, so let’s get back to our main thread.

Flicks that adapt their source material dominate the U.S. movie industry because people tend to enjoy them, or at least they’ll buy tickets to known quantities. For better and certainly for worse, familiar plots and characters put butts in seats, which is why a lot of the top-grossing flicks and series are adaptations. To some extent we rank-and-file moviegoers have to watch what the studios serve us. Still, consider a mere gaggle of those top-grossing flicks: the Marvel movies, Gone With the Wind, The Lord of the Rings, James Bond etc., Harry Potter et al., the Jurassics (both Park and World — a sequel to an adaptation is still an adaptation, this is my newsletter, I make the rules), Doctor Zhivago, The Sound of Music, the Fast/Furious fracases (the first one was inspired by, if not literally adapted from, a magazine article), Beauty and the Beast, The Ten Commandments (basically, c’mon). That’s a lot of ultra-money-printing adaptations! Plus, not a few of the most esteemed American movies adapted their stories: The Godfather, Citizen Kane, Vertigo, and 2001: A Space Odyssey are based on a book, a person, a book, and a book, respectively. Even Titanic was pitched to studios as “Romeo and Juliet on a big friggin’ boat.”

The list of ultra-money-printing flicks with original stories, on the other hand, is smaller, including: The Lion King (despite its basically being Hamlet — let’s call it Hamlite), various Star Wars installments (which feel like they’re based on something at this point, but maybe it’s just decades of pop culture omnipresence), Minions & Co., The Incredibles, arguably Frozen (which started life as a take on a Hans Christian Andersen tale before finding its own path), and, sigh, Avatar.

Having said all that, why do we adapt things? There’s the financial windfall from turning a popular novel into a popular flick, doi. There’s the difficulty of coming up with a good idea (really difficult!), which means if someone else already had a good idea, you might as well repackage it and sell tickets. There’s the impulse to bring a quality tale to an audience of millions, though studio bosses are mostly doing it, as we’ve said, because they think the story will sell.

But what is an adaptation, really? It’s not just the original version with a new haircut. It’s a version better suited to another medium or format, to its rhythms and structures and genres and tropes. A movie based on a book isn’t a book, can’t do what a book can do, shouldn’t bother trying. Books are good at some things and bad at others, just as movies are, just as songs are, just as paintings are, just as plays are. When a book becomes a movie, invariably not every character, scene, plot line, and location make the cut. They can’t — a book can last any number of pages and unfolds at the speed of the reader’s eyeballs. A movie lasts 100 or so minutes and unfolds at 24 frames per second.

In other words, books’ stories don’t have the forward momentum that movies’ do, because movies exist in the viewing. They’re like music that way — a song only exists when it’s being listened to, when the notes or chords are coming one after the other for three to four minutes. Similarly, a movie is a movie only when its frames are flickering fast enough that your eye is fooled into seeing motion. (Or, you know, when the digital video file is projected on the theater wall.) Sure, books are made of words the way songs are made of notes, but the words go by at a speed of your choosing. With a book you can stop reading for the night, flip back to reread a page with amusing dialogue, check the list of characters to remind yourself whose rich uncle that is. The reading experience is literally in your hands and up to you. With a movie there’s no flipping back — the flick keeps playing whether you’re looking at it or not. Plus, I almost never read a book cover to cover in one sitting; I almost always watch a movie start to finish without stopping. A book that’s halted feels naturally paused; a movie or a song that’s halted feels interrupted.

This difference in momentum affects how the story can be told. In a book, for example, an author can throw a lot of exposition at a reader, and as long as it’s written well, who’s who and what’s what probably come across naturally. In a movie, exposition bogs down the forward motion, which is why you often feel screenwriters grasping for ways to give us information without us noticing. (A voiceover explaining who’s who? A radio or TV broadcast setting up what’s what? One character saying to another, “Wait, you didn’t hear what happened last night?”) There isn’t really a limit to what a book can do that way, or at least the limit is the writer’s talent. Reading is like listening to a storyteller by a fire: you want them to get to the point before too too long, but you’ll be patient if the company is good. A movie, though, is like a storyteller you’ve hired for 100 minutes — it’s entertainment on deadline. Whatever happens, wherever the story goes, whatever you understood or didn’t, in 100 minutes the storyteller has somewhere else to be, so you’d better listen up.

But also, significantly, even though a book is written by an author, in some ways its story is written by you. When you read a book, some magical alchemy happens whereby words on a page become an honest-to-god story in your brain. The author may give you the text, but your imagination strings the words together to bring them to life. With a movie, though, you sit back and let someone else’s pictures wash over you; you observe what someone else imagined. That’s one reason adaptations of beloved books can feel jarring: a story you thought was a close friend turns out to look like a stranger.

So, that’s some philosophizing about what an adaptation is. Now, what makes a good adaptation? Note this isn’t the same question as what makes a good movie. Can a bad movie be a good adaptation? Sure! Can a bad adaptation be a good movie? Sure! The quality of the adaptation, I warrant, has to do with the flick’s take on its source material, not how well the final product turns out.

The obvious answer is that a good adaptation somehow captures the book’s spirit, its raison d’être. It tells a version of the story that the book tells, and it uses elements from the book — characters, story beats, dialogue, themes — to craft a flick that has things in common with the book but doesn’t try to be the book. (Related question: can an adaptation of a graphic novel too closely replicate the novel’s visuals? Did you see, say, Sin City or Watchmen, which recreate panels from their books? Discuss.) And what exactly does it mean for one expression of a story to have things in common with the original expression? I’m not fully sure, because turning one format into another is a mysterious idea. Outside of entertainment, when do we even do it? Can you turn a meal into clothing, a color into furniture? Maybe you’d argue that pistachio ice cream is an adaptation of pistachios. Maybe you’d be right.

Believe it or not, I have yet more thoughts on what an adaptation is, but I’ll save them for the next time we’re having a beer together, because I want to get to a few notes on the adaptations I’ve seen lately. But real quick, here’s my attempt at defining a good movie adaptation: it tells a story whose arc you recognize, whose characters you recognize, whose themes you recognize, and whose details have enough of the book’s flavor that you recognize them, too. Maybe all that is obvious, but I still find myself grasping for exactly why one story would ever feel like another, and that’s the best I’ve got. And note I said that you recognize those elements, not that they’re identical to the original’s.

And just in case anyone asks, my favorite adaptations that I’ve written about in these pages are Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (uses the graphic novel’s themes, visual cues, and pop culture motifs but invents its own story structure), Ran (uses the arc and classic scenes of Macbeth but drops Shakespeare’s poetry and adds Japanese history), and Akira (somehow squeezes the arc of a graphic novel series into two hours of cohesive apocalyptic mayhem). Oh, oh, and I can’t miss this opportunity to plug Adaptation, a 2002 movie that’s one of my all-time faves. It’s about the horrors of the creative process, it has Nicolas Cage playing identical twins, and you should definitely see it.

OK, in no particular order, here are the five adaptations Josh watched and wanted to write about…

Dune (2021)

What it adapts:

Dune, a sprawling sci-fi fantasy novel of galactic political strategizing from 1965. It’s too complicated to explain in one sentence, but…there’s a desert planet where a naturally occurring substance enables faster-than-light travel, so rich families from other planets obviously fight over the rights and profits of harvesting it, and also there’s a group of space witches who have been trying to produce a space messiah, and it turns out the son of the rich family who just took over the harvesting might be the messiah, who’s also the messiah of the desert planet’s oppressed indigenous people, and everyone is going to need a messiah soon because the son’s family was betrayed by the galactic emperor right after taking over the harvesting. Got all that?

Adaptation rating:

7/10

Movie rating:

6/10

Why?

A few weeks ago I read a review of Dune where the critic had seen the flick with a friend who was a huge Dune fiend. After the credits rolled, the friend started freaking out, saying, “That was exactly the movie I saw in my head!” And that’s why the new Dune flick is a so-so adaptation for me — a boring one, really. I like the book well enough (I read it once, when my high school science teacher gave me a copy), but the new movie is more or less exactly what I imagined, too. For the friend, apparently, having his expectations met, if not exceeded, was exciting; for me, I wondered Is that it? You didn’t have any ideas for this that I didn’t have? The performances are fine, the story is fine, the music, the action scenes, the cinematography — all fine. But does “fine” make for “good”? (By the way, everyone keeps talking about how beautiful Dune’s cinematography is, but is the camera doing anything besides showing us the deserts of Jordan and Abu Dhabi? Is the movie beautiful, or are Jordan and Abu Dhabi beautiful? Is there a difference?)

I said “the new Dune flick” above because, as you may know, this one isn’t the first. In 1984 David Lynch directed a Dune adaptation that’s famously bad, though the studio famously took the movie away from him and recut it before the release, so I doubt the final product is Lynch’s fault. But! His Dune is at least weirder than the new one, which is directed by Denis Villeneuve, a director I’m normally very into. Maybe I’m wrong, but I think a Dune movie should be a little weird! Did you read the part about space witches and space messiahs? Also, the rich family’s son starts to see visions of the future after ingesting the desert planet’s naturally occurring substance. That’s some weird potential! But for my money, the new Dune is staunchly anti-weird. It’s too much a dour, straightforward clone of other space action movies. It does an admirable job of fitting half a complicated book into one movie, but so much of it is so…obvious. If I’m being honest, it’s too much like Star Wars, another movie about a boy on a desert planet who gains magic powers and leads a revolt against the galactic empire. I’m not saying an adaptation has to be weird to be good, but in a world where Star Wars came out 44 years ago, you’ve gotta give me more, Villeneuve.

You’ve probably heard there’s going to be another Dune movie in a few years, since the new one only tells half the book’s story. I doubt the second flick will be wildly different from the first, but I live in hope. Villeneuve is definitely capable of weirdness — he directed Blade Runner 2049 and Arrival, both of which have suitably weird flourishes, and if you’ve known me for more than a few hours, I’ve probably recommend that you watch Enemy, another Villeneuve movie that’s plenty weird. Anyway, we’ll see.

The Green Knight (2021)

What it adapts:

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a medieval epic poem about an underachieving knight. On Christmas one year, an entity called the Green Knight visits King Arthur’s court and suggests a game: someone there can strike a blow against the Green Knight if, one year later, the entity can return the blow in equal measure at his faraway Green Chapel. The underachieving knight cuts off the Green Knight’s head to hearty applause. Then the entity calmly picks up its head, reattaches it, says, “Cool, see you in a year,” and rides off. The underachieving knight gulps.

Adaptation rating:

9/10 (I’m guessing)

Movie rating:

8/10

Why?

Admittedly, I haven’t read the epic poem, so I don’t have anything to compare the movie with. But Wikipedia tells me their stories are fairly different in significant ways: whole sections of the movie are invented, the main character’s race is changed, the ending is super different. Writer-director David Lowery took the poem, which alludes to some of Gawain’s adventures without detailing them, and fleshed it out by showing the spooky stuff the knight gets up to on his merry way. That fleshing out was basically required if the movie was gonna be more than half an hour long, and I was interested that it wasn’t clear exactly how each adventure aligned with the story’s themes.

Weeks after seeing the flick in Vienna, I have a bunch of questions about what X, Y, and Z mean and why A, B, and C had to happen that way. Like, it seems like Gawain’s mother, a witch of some kind, conjures the Green Knight, something that doesn’t happen in the poem. (I haven’t spoiled anything beyond the first scene, don’t worry.) But go see the movie and then let’s talk about whether its version of the story would unfold any differently if she didn’t, if the Green Knight simply appeared from lands unknown. Normally I’d fault a movie for this kind of thing, call it jumbled or (the Josh Watched cardinal sin) not thought-out enough. Here, though, the vagueness made me want to see The Green Knight again. It’s not that I think I missed anything revelatory per se; it’s more that Lowery crafted something I haven’t figured out yet and am still enjoying thinking about. That’s a good adaptation in my book.

The French Dispatch (2021)

What it adapts:

The New Yorker, in that The French Dispatch is divided into sections that sort of, roughly, correspond to the sections of that notable American middlebrow magazine, and in that the Dispatch’s staff is known to be based on storied New Yorker writers of yore. Incidentally, the editor played by Bill Murray is the kind of editor I’ve always wanted to work for.

Adaptation rating:

9/10

Movie rating:

7/10

Why?

The picture is an ode to a magazine — to an exploratory style of writing, to a worldly curiosity and spirit, to a familiarity with a range of intellectual pursuits — in the form of a movie. Often artistic homages take the same form as the thing being homaged: a song covers another song, a movie borrows visual cues from another movie, a photography series references another series. You could imagine an ode to The New Yorker being an actual print product, or maybe a website — something based in text. That’s why Dispatch really worked for me as an adaptation even though I didn’t love the movie: unlike Dune, it surprised me. (Like Dune, some of its sections are a bit dull.) It’s a flick that does a pretty good approximation of watching The New Yorker rather than reading it.

Metropolis (1927)

What it adapts:

Metropolis — one of the great silent flicks, and one of the best movies ever, full stop; you should absolutely see it once in your life, ideally with live music, which is often how it’s screened these days — was written by Thea von Harbou, who adapted it from her novel of the same name. I haven’t read the book, but my understanding is that its story isn’t far off from the movie’s: a huge futuristic city is run by the elites. The working class operates the machines that run the city underground. They’re on the brink of revolt over their working conditions. The son of the elite’s leader has his eyes opened to their plight. He works to mediate between the two groups before the city tears itself apart. Meanwhile, a scientist with a grudge against the elite’s leader uses a robot disguised as the workers’ spiritual leader to stir the pot.

Adaptation rating:

9/10 (I’m guessing)

Movie rating:

10/10

Why?

The story is a thin class parable that isn’t really the point. The point, which you’ll see as soon as the movie starts, is the gobsmacking production design. The way the 1927 flick conjures a supercity out of, I’m assuming, scale models and smoke and mirrors is amazing. There are plenty of CGI-powered colossi from the last decade that don’t look this good. Another visual thing is the crowd scenes, which have hundreds of bodies in kinetic motion, running riot or turning the huge gears of industry in beautiful synchronization. Today it’s not uncommon for a movie to hire a few dozen extras and digitally fill in a cast of thousands, but a hundred years ago the only option was to hire the number of bodies you needed, and that approach gives the crowd scenes an organic vitality that’s probably unlike anything you’ve seen before. Metropolis is a great adaptation because it seems less interested in the coherence of its story — an ideological trifle with a bunch of quasi-religious Book-of-Revelation gobbledygook — and more interested in using the story as something to hang the visuals on. But those overwhelming visuals (and the gonzo story too, if I’m being honest) are also what make it a great movie.

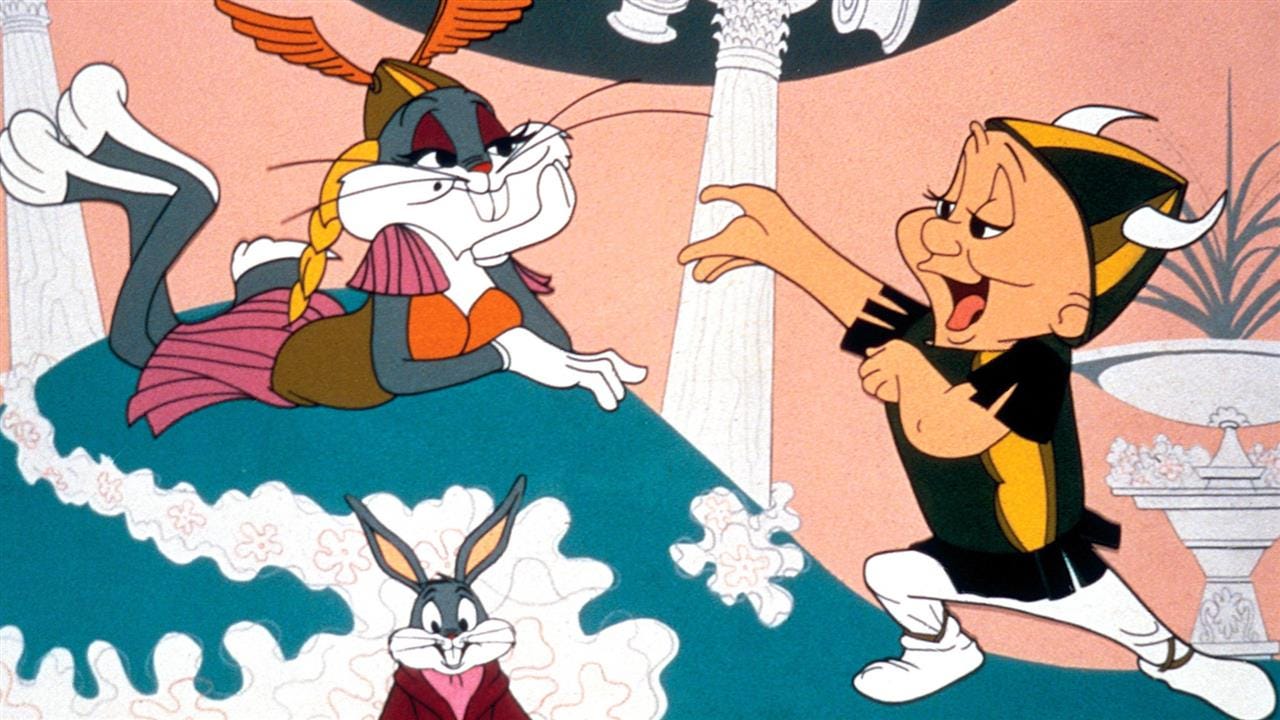

Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance (1921)

What it adapts:

Hamlet. Heard of it?

Adaptation rating:

10/10

Movie rating:

10/10

Why?

It uses the arc and characters of the play but adds a ton of new stuff. For one thing, the flick’s conceit is that the brooding Danish prince is so brooding because he’s secretly a woman. In this telling, the king and queen needed an heir, so they decided their daughter would live her life passing as their son. Also, the movie shows Hamlet at university, where she meets Horatio and Fortinbras, scenes that are nowhere in the play but that really worked for me — they’re not the Hamlet you know, but they set up what’s to come in a fascinating way.

There’s more, but the regendering of Hamlet alone adds so many juicy emotional dynamics. A big one is that she’s in love with Horatio, but Horatio thinks she’s one of the guys and is himself in love with Ophelia, so Hamlet pretends to woo Ophelia to keep her away from Horatio, and on and on. Everything about Hamlet’s dark disposition takes on new meaning since the prince’s whole life is a disguise. When Hamlet comes home to find Gertrude has married her uncle (a scene where Asta Nielsen, in black clothes and cape, looks awesome), she feels doubly betrayed. It’s not just that her father has died and her mother doesn’t seem to miss him; it’s also that Hamlet’s two-timing mother is now the only one who knows her secret. If you like Shakespeare, Hamlet, silent movies, gender stuff, or German flicks, this take on the Bard is essential viewing.

And that’s it for this edition! Thanks for reading, and look out for more from me soon, Barcelona café gods willing. I just saw my 151st movie of 2021 (my record for a calendar year is 153), and I’ll be breaking down the numbers and handing out the inaugural Josh Watched awards (the Joshes!) in a few weeks.

Until next month!