Josh Watched #23: Mulholland Drive

Hi! As the previous edition promised (or maybe threatened?), this month’s newsletter consists of some good old-fashioned film analysis. We’ll be analysis-izing a favorite gonzo flick of mine: Mulholland Drive. Your homework, recall, was to watch Mulholland Drive in its two-hour-plus entirety. Did you? If not, you really should before reading on. You don’t want to fall behind the class. (Also: spoilers!) Go ahead, watch it now, I’ll wait — just give me a shout when you’re back.

OK, everyone here? Groovy. Sharp readers such as yourselves may be wondering how “film analysis” differs from what usually happens in Josh Watched. To some extent you’ve got me there, reader — I often use this space to write about movies’ themes and story constructions and technical elements. The difference this month, I’d say, is in the depth and purpose of the interrogation. When Josh Watched launched in the long-ago prepandemic world of February 2020, each movie I wrote about received just a few paragraphs, mainly aiming to explain why the flick was worth 100-ish minutes of your life. I was recommending movies — specifically ones you might not have heard of — with enough context to pique your interest and give some idea of what you were in for.

Is that film analysis? Mmm not quite. We might say Josh Watched was originally about describing movies more than analyzing them. (In fact, I would say that.)

A film analysis, for me, is an attempt to understand how a movie works as a constructed piece of art, or at least a constructed piece of entertainment, or at least how it’s supposed to work. An analysis is about connecting the dots between all of the movie’s elements, onscreen and sometimes off, to understand how they contribute to the whole, why someone chose to include them — spent money to include them — in the picture. Movies are made of choices, after all, thousands of them: the story is about this, the story’s scenes will unfold in this order, the main character will wear this shirt in the first scene but that shirt in the third scene, the music will sound like that, there won’t be music in this scene, the tone of what’s happening will create that mood, her big line of dialogue will have this emphasis, and so on and so on.

Not every decision is core to the movie’s inner workings, and that’s OK. (Like, maybe a costumer decided the main character would wear blue when he’s introduced because, well, he had to wear something.) So a good analysis identifies what’s most important to or salient in those inner workings. (Like, maybe characters’ clothing colors tell you something about their roles in society.) You might not find definitive answers for every element, and that’s OK too; god knows there’s plenty of stuff in Mulholland Drive I can’t explain. But even if we don’t know why the shirt is blue, we can still observe the effect it has on both us and the movie. (Like, maybe the flick is full of blue hues because a cool visual palette supports the story’s themes.)

I think of film analysis as cracking open a piece of machinery to see how all the cogs and levers and gears connect, how they work together to, say, help the machine tell time. The film analysis is the diagram of the machine’s parts. You can still use the machine to tell time without knowing how it works; some of my favorite flicks wash over me in a blissful wave while I’m forgetting to analyze them. But I find that peeking under the hood gives me more respect (or, sometimes, less) for the craftspeople who crafted the movie. Remember how flicks are made of thousands of choices? That means it’s basically a miracle that any picture ever turns out well — and that means it’s our duty, as thoughtful, ambitious filmgoers, to understand why the good ones are any good.

All that said, the two core questions of film analysis (according to me) are: 1) What am I seeing? and 2) Why am I seeing it? Keep in mind that, ideally, every element of a movie should feel visually and thematically cohesive, of a piece — unless, of course, lack of cohesion is the point. So when it comes to that second question, Why am I seeing it?, there’s a decent chance the “whys” of various parts of the movie are connected.

And with that, let’s analyze Mulholland Drive! (You did watch it, right?)

Mulholland Drive

OK, so where do we start with a film analysis? I’d start with what you notice when you watch the movie: the story? The acting? The camera moves? The costumes? The lighting? The visual motifs? What draws your attention, and why? (In other words — you guessed it — what are you seeing? Why are you seeing it?)

I like to start with the story, since few things interest me as much as story construction. Mulholland Drive, for me, has a number of juicy entry points we could bite into: the characters, the music, the colors, the ~vibe~, the flick’s place in the director’s corpus. (David Lynch, who wrote and directed, exemplifies my theory that the careers of certain directors circle around a few themes and ideas, and their oeuvres build up to a few pinnacle movies that stand as those ideas’ peak expression. A lot of the stuff Lynch has done — Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet, Eraserhead — is concerned with identity, dreams, the supernatural, what-ifs, what-could-have-beens, mystery, love, falling out of love, the horror lurking beneath the everyday. Not for nothing, his work also relies too often on violence against women as a plot point.)

But the story of Mulholland Drive, for me, is the place to start, because a common response when the credits roll is “It made me feel things, but what happened?” And besides, narrative analysis is my hobby horse, so let’s get galloping.

Thusly, what can we say about Mulholland Drive’s story? It takes place in Los Angeles. To some degree it takes place in Hollywood, both literally and as a state of mind. It’s about the movie industry, acting, ambition, why some people get ahead and others don’t. It stars two women, one an aspiring actress, the other an amnesiac; it stars two women, one less successful, one apparently a star. It exists in a world of mysterious connections and hidden power, of people who pull the strings behind the curtain. It’s about the bad things people do, both visible and not.

What else about the story? That’s right, reader — it’s weird! Some sections of it are straightforward, and others trip down narrative rabbit holes. Some scenes play as comedy, others as mystery, others as horror. (What did you make of that diner scene at and behind Winkie’s?) Some characters seem to have two names, or maybe the same actors are playing multiple characters. Symbols, locations, lines of dialogue all repeat. And then there’s the turn the story takes with about half an hour left, when the camera zooms into the blue box and emerges…somewhere else? Somewhen else? Somewho else?

It seems to me that the turn is pivotal to unlocking what the story is about. And there is something to unlock, right? Clearly, the final 30 minutes or so aren’t the same story we’ve been seeing up to then. Suddenly, everything — characters, names, relationships — is a little different, or a lot different. The world becomes more menacing, bleaker, harder, grayer, colder. Why? What happened?

One popular theory — a theory I’m not a fan of, and am about to argue against — is that most of Mulholland Drive is a dream. In this reading, Diane Selwyn came to Hollywood to make it as an actress, she fell in love with Camilla, Camilla helped the less-successful Diane with her career, Camilla left her for the movie director Adam, and Diane — in her grief and anger — hired a hitman to kill Camilla. The first two-hours-ish of the movie, then, are thought to be a dream the drug-addled Diane has post-hitman-hire, as her brain grapples with the enormity of what she’s done. That’s why characters, names, symbols, and so on repeat — Diane’s subconscious is remixing reality into something bearable. In this remix, Rita/Camilla is wholly dependent on Betty/Diane; Betty/Diane is a more innocent, pre-murder version of herself (with a plucky, can-do Nancy Drew attitude); and the two women are together again. Once Diane wakes from the dream, the theory goes, her guilt and grief lead her to shoot herself, ending the movie.

Two things people point to in support of the dream theory:

The second shot of the movie, after the jitterbug dance intro, is a first-person shot of someone falling asleep in a red bed, a bed that two hours later we see Diane waking up in (after the Cowboy says, “Hey, pretty girl, time to wake up”). In theory, these two events are the bookends of the dream.

Club Silencio, the theater Betty and Rita go to in the middle of the night, is often held up as a metaphor for the unreality of the dream. As you’ll recall, the performance includes a bunch of references to illusions, to things not being real, to music playing despite the lack of a band (“It is all a tape recording”). When Betty starts shaking violently in her seat, it could be because Diane has been confronted with the falsity of her illusion.

What say you to the dream theory, reader? Does it make sense? Does it feel right?

I say: meh. For one thing, and most importantly, summing up the movie as “It was all a dream…” is just too easy, which is to say, boring. For another — reader, I don’t know if you’ve had dreams before, but they’re famous for being a bit wacky. Mine sure tend to be weirder than reality, on average. And for me the last 30 minutes of the flick (the “reality”) are a lot more dreamlike, more nightmarish, less narratively straightforward — less linear — than the first two hours (the “dream”). If anything, the last 30 minutes, with their chopped-up chronology driven by Diane’s emotions and memories, feel like the funhouse remixed version of her life. The first two hours just seem like life, albeit in a Los Angeles that’s occasionally surreal and horrific (but hey, that’s LA for you).

For another thing, I think there are as many pieces of textual evidence against the dream theory as there are for it. Crucially, the shot of someone (probably Diane, but we don’t know for sure) falling asleep in the red bed isn’t the first shot of the movie — it’s the second. The jitterbug scene takes place before, and thus outside the realm of, the supposed dream, which means the jitterbug scene doesn’t fit neatly into the dream theory. So what are we supposed to make of that scene? Is it a coincidence that it’s the opening shot of the flick?

Believe it or not, reader, I’m trying to keep this analysis short, but there are three points I want to make about the dream theory.

There seem to be explicit, tangible links between the two stories — Betty’s and Diane’s — that are more complicated than just Diane going to sleep and waking up. For example, something definitely shifts when the camera zooms into the blue box with 30 minutes left — immediately, Rita disappears and Betty’s aunt walks into the room, though she’d left LA earlier in the movie. For her to now be in the apartment, and Betty and Rita to not, suggests we’re not in the same apartment from moments ago. And let’s not forget the zooming into the blue box itself — something happened there. The box is then mirrored toward the end of the flick, when we see that the figure behind Winkie’s also has a blue box; again, this is after Diane has woken up, so we’re in the “real” world. So, both stories have a blue box and both have a blue key. Is it possible the two stories unlock each other?

If someone tells me Club Silencio is a metaphor for the illusion of Diane’s dream, my answer has to be that we see Silencio again at the very end of the flick, after Diane has woken up, after she shoots herself. I read this as the flick telling us Silencio is in both worlds, in both stories. Why show it again otherwise? For me, Silencio’s meaning is larger than just revealing the existence of a dreamworld; it has to do with illusions on a broader scale. In fact, the woman with blue hair whispering “Silencio” is the last shot of the entire movie, which would seem to bring the idea of illusions to bear on the entire flick, on both stories.

Within the first two hours of the picture, “Diane’s dream,” we see Rita go to sleep several times, which raises questions about what happens while she’s sleeping. That awful scene at Winkie’s, the first time we see the figure in the alleyway? It happens while Rita is asleep. Notice that right after the diner guy sees the figure and passes out, we see a quick shot of Rita, still asleep. Is that an accident? Later scenes also happen while Rita is sleeping. And recall that in the second shot of the flick, we never see who is going to sleep in the red bed — is it possible some/part/all of this is a dream? If so, whose?

I’ll tell you what I think Mulholland Drive is about, reader. To that end, I’m going to do something I never thought this newsletter would: invite you to watch a short film I made in grad school. The assignment was to come up with a conceptual short about Los Angeles, one that engaged with the theoretical texts we were reading about movies and LA and modes of representing reality. The books I was most interested were those that explored Los Angeles as a place of layered reality. There’s the real city with real people living real lives, there’s the entertainment factory of Hollywood that manufactures fiction within the real city, there’s the manufactured version of LA — all the stuff that’s “happened” in the city because it happened in movies and TV shows about the city — and we could probably think of a few more layers, such as the history of the city and region before the U.S. took it over and since.

The result of this layering, for me, is that living in Los Angeles feels like living in two worlds. (New York, which has appeared in innumerable movies and shows, has a similar thing going on: “Hey, isn’t that the street corner where [some completely fictional event] happened?”) If what I’m describing interests you, I’d definitely check out Thom Andersen’s fab 2003 documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself, which traces the city’s history onscreen. For now, I’ll just refer you to my (much shorter, iPhone-filmed) 2013 attempt at capturing the same idea: “The Secret Spots in Hollywood.” If you can’t tell what my voiceover is saying, the words are in the video description. (Fun fact: after I screened the short for my classmates, a girl I had a lil crush on said my voice reminded her of Werner Herzog, the German director with the famous voice, which is ludicrous but is also the best compliment you can give someone in film school.)

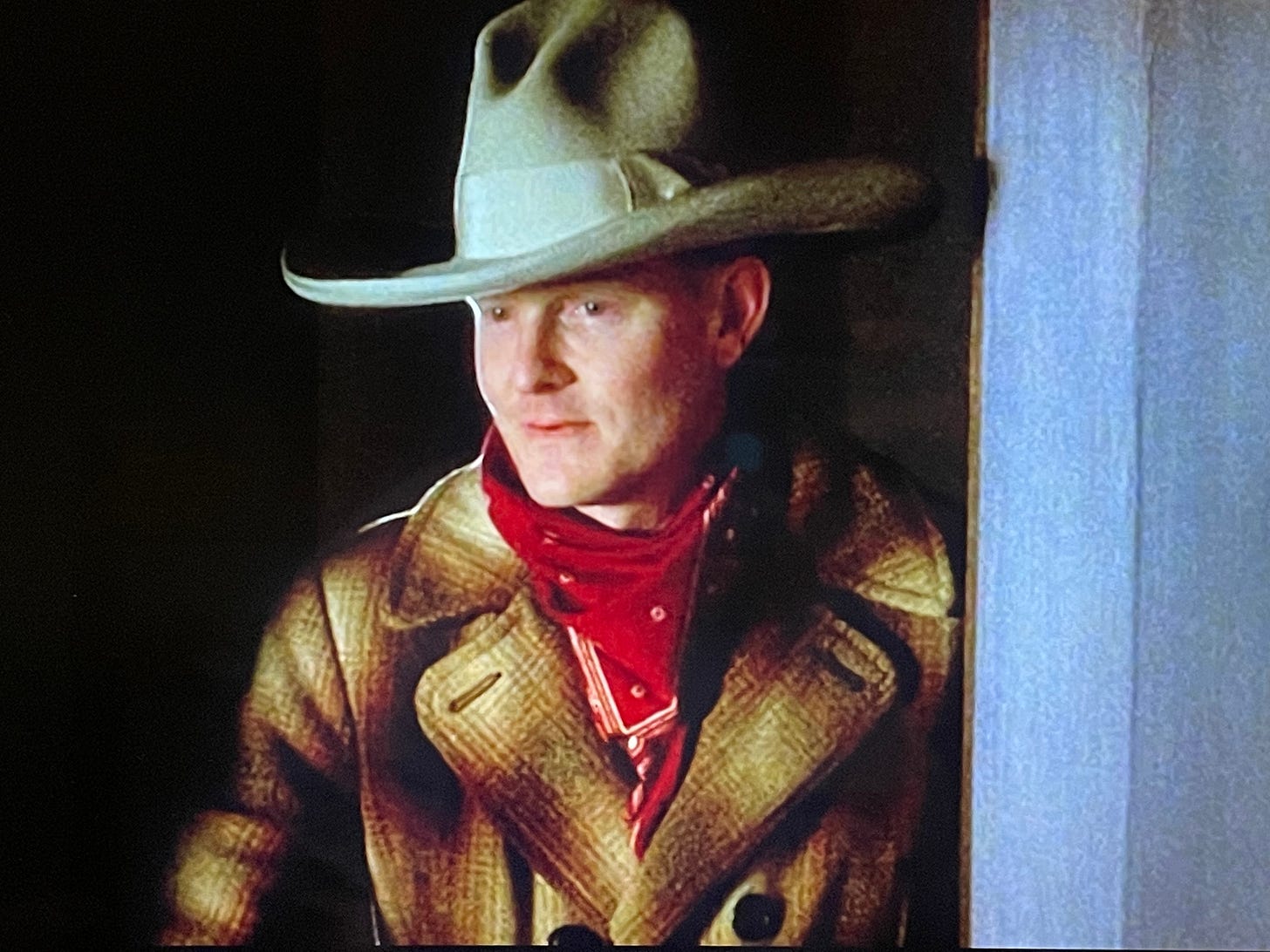

So. I think Mulholland Drive is about the layered nature of reality in Los Angeles. I don’t think the flick is meant to be a dream-story contained within a “real” story. I think both stories are real; they’re versions of each other, two sets of histories and futures, two collections of people and events and relationships that could happen, did happen, might happen, will happen. The two stories aren’t parallel universes in a sci-fi sense; they’re two possibilities existing in the same place. They’re two lives that started the same (with the jitterbug contest — the first scene in the flick, and arguably the event that brought both Betty and Diane to Hollywood) before diverging wildly. I think Mulholland Drive is about two overlapping, connected stories in a city where many more stories are constantly taking place and being manufactured, where the real and the imagined coexist side by side, where one audition can change your life, where one project can introduce you to your future lover, or your lover to the person they leave you for.

I’m almost done, reader, but there’s something else I can’t not mention while writing about Mulholland Drive: my very favorite flick, Sunset Boulevard. I’ve written about Sunset in these pages before (and I’m often on the verge of doing so again), and in some ways the two movies are spiritually linked. They’re both about Hollywood, both named for famous streets in Los Angeles, both dark as hell, both about how the search for fame can twist people beyond recognition. Lynch has even said Sunset is his favorite movie. (Years ago, in Los Angeles, I saw the two flicks in a double feature. Squee!) Since you’ve now watched Mulholland, you could do a lot worse than watching Sunset too and seeing what strikes you. If you need someone to watch it with, text me, I’ve got time.

Of course, I could be totally wrong about Mulholland Drive — in which case, who the hell knows what this flick is about. One thing I do know is that Lynch never gives you all the answers and his work defies easy explanation. (That said, for the DVD release of the flick, he offered viewers 10 clues to the story. Are they real? Who can say? Sometimes the weird stuff in Lynch just is.) So it’s a good idea to watch his stuff without trying to connect all the dots. What’s that, reader? I started this edition by telling you that’s exactly what film analysis does? Well, film analysis is also about finding your own interpretation of a picture, critical opinion be damned, so don’t hesitate to disregard mine. But if you have your own ideas, I’d love to hear them.

That was a lot of thinking about a stubbornly oblique movie, so let’s wrap up here. But I’ll be back in your inbox soon with a short edition. I miss you when we don’t talk.

Thanks for reading. Until next month!