Josh Watched #25: January 2024

Hi! Let’s kick off season 4 of Josh Watched with a question, and a personal bugbear.

When you do your job well, reader, do you expect awards to follow? I’m not talking about a modest “Good job” or a tidy “Bravo.” I mean something above and beyond — a cash prize, say, or a golden trophy handed to you while peers look on enviously. I ask because if you’re like me (God help us), you don’t expect people to fall all over themselves just because you did the thing. Yet that’s often the attitude in Hollywood, which, you may know, is in the midst of that annual paean to pomp and puffery: awards season.

And if it’s awards season in Hollywood, there’s one thing you can be sure of, gentle reader: Bradley Cooper wants an Oscar. Or, preferably, several. See, Cooper has been around for a while as an actor; you may know him from the Hangover movies or Silver Linings Playbook or American Sniper. (Most of what I remember about the latter is the keen creative choice to give Cooper’s character a doll instead of a real baby.) In recent years, though, Cooper has made the jump to directing, and also to other creative pursuits, which is why you may additionally know him from A Star Is Born, a movie he directed, cowrote, starred in, and sang in. A real multi-hyphenate, as they say in the biz. I thought A Star Is Born was fine; Cooper and Lady Gaga, who played opposite him, were decent, but the movie was nothing to get worked up about.

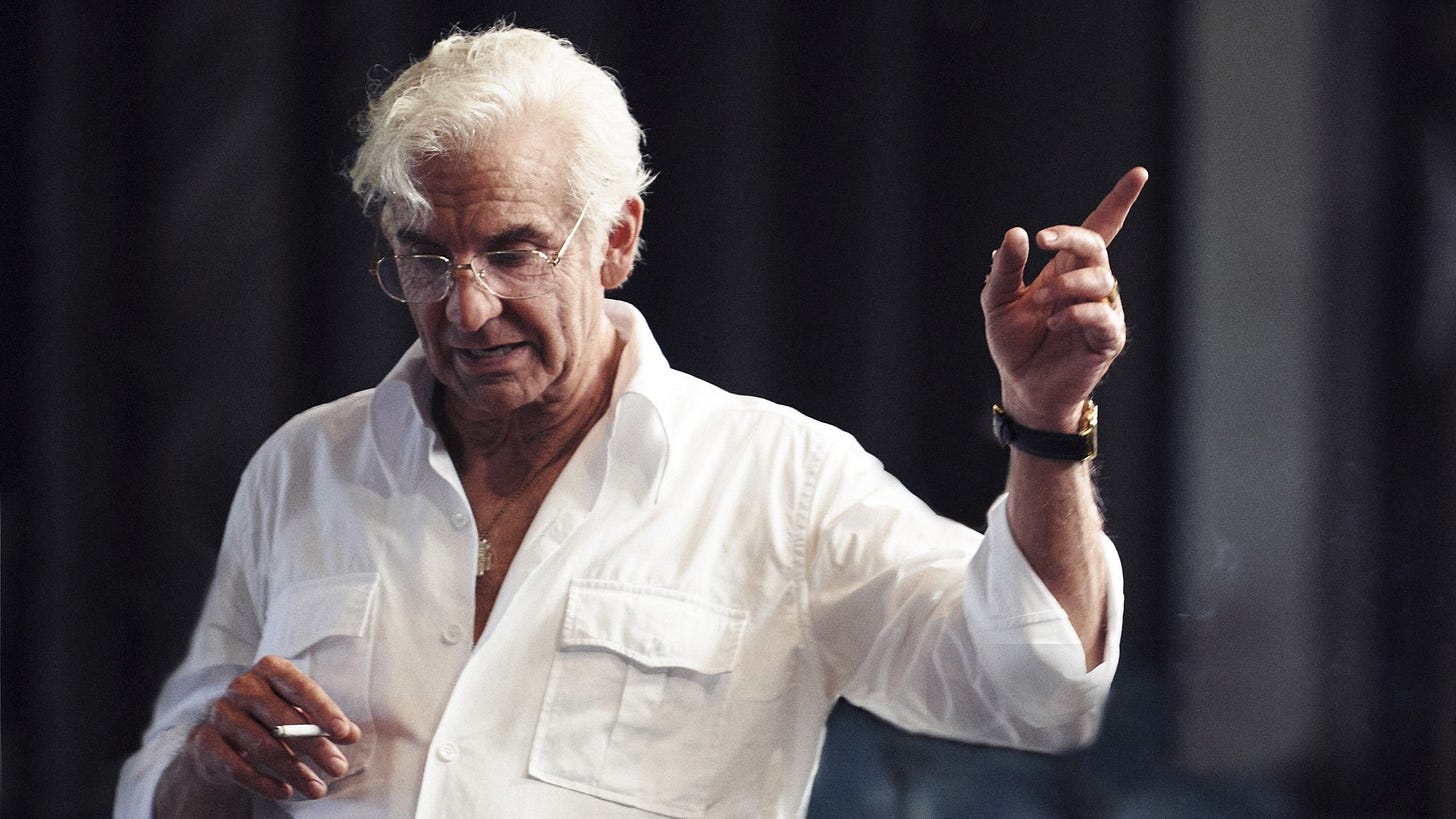

Ditto Maestro, Cooper’s new flick (directed, cowrote, starred in) about the life and times of Leonard Bernstein, the conductor and composer. The movie has been Cooper’s passion project for years, and with his, ahem, star rising, he finally had the juice to get it made. Reviews have been moderately to pretty good — he’s a promising director, though for me his artistic reach still exceeds his grasp — especially regarding Carey Mulligan, who (luminous, as ever) plays Bernstein’s wife. The thing is, Star and Maestro are both…“Oscar bait” is a played-out term, so let’s try Oscar-leaning. There’s a sense among some minds in the industry that Cooper’s two movies — in their beats, their themes, their big emotional moments — may be built to appeal to Oscar voters just a tad too much. There’s equally a sense that Cooper wants an Oscar real bad, and Academy voters are fickle folk: they want you to want their trophy, but, like, don’t embarrass yourself about it.

So it’s schadenfreude-ly fun to wonder whether Cooper’s thirst for gold cost him a Golden Globe a few weeks ago, when he lost to Oppenheimer’s Cillian Murphy. (There’s zero crossover between the voting bodies of the Globes and the Academy Awards, but still.) Equally fun is wondering what that result might mean for the Oscars showdown. Cooper had been nominated for nine Oscars before this year; he didn’t take home any of them. Hilariously, the one Oscar that Star did win was for “Shallow,” the ubiquitous-in-2018 smash single that Cooper performed but didn’t write — so no trophy for him. Maestro picked up seven nods in this year’s nominations, with three of those for Cooper (Best Picture, Best Actor, Original Screenplay), so stay tuned; the ceremony is March 10. And look: I don’t have a horse in this race. I just want all my favorite movies to win Oscars and all the other flicks to lose. But as I count the movies that Cooper has directed so far — Two. He’s only made two of them — I can’t help thinking: wasn’t it once an honor just to be nominated? Can’t you just make a decent movie and have that be that?

And so we come to Barbie. Those of you who’ve been online since this year’s Oscar noms were announced on January 23 have heard the laments of the pink-clad faithful, that Greta Gerwig wasn’t nominated for directing Barbie, nor Margot Robbie for bringing the plastic doll to flesh-and-blood life. Both were nominated in other categories (for writing and producing, respectively), and the picture got eight nods overall. Some observers, though, think that wasn’t enough, especially since Ryan Gosling was nominated for playing Ken in a movie about feminism and patriarchy. Personally, I don’t have an issue with Robbie’s “snub” (a word I detest); she was solid as Barbie, but for me the movie’s accomplishments are in its concept and execution, not its acting. And while I don’t think anyone “deserves” Oscars recognition (see above about “snub”), I probably would have given Gerwig one of the five directing nominations over, say, Martin Scorsese, whose Killers of the Flower Moon falls into the “fine, but not really sure this needs a trophy” camp. I wouldn’t have nominated Gosling or America Ferrera, whose Best Supporting Actress nod, I suspect, is mostly about that big speech at the end, which is more about the writing than the acting — and hey, Gerwig did get a writing nod.

But what’s the difference, you may be wondering, between Gerwig and Cooper? Why does one feel like a “snub” and the other not?

I suppose it’s about whose artistic vision impressed me more. I wasn’t even head over heels about Barbie, reader. I liked the first half fine, but in the back half I had the irking feeling that none of what was happening really existed and nothing was truly at stake. Sure, the story is more nuanced than that, and yet…it all felt too corporate, too “let’s impose a narrative on Barbie.” True, I don’t have an emotional attachment to Barbie (though I did play with my sister’s), but when I unscientifically surveyed a handful of female friends, neither did they; they all thought the movie, or perhaps Mattel, overhyped What Barbie Means. We’re hardly a representative subsection of the populace, and I did appreciate the flick’s excavation of Barbie’s checkered history. Yet somewhere around the beach war scene, the whole thing started losing steam. The picture is still a good effort; it’s not hard to imagine how bad a Barbie movie could have been, so to make something surprisingly smart that’s also the year’s biggest box office smash ($1.4 billion!)…therein lies Gerwig’s achievement. Even if the picture didn’t fully work for me, there would be, as Gosling put it after his director’s “snub,” no Barbie without her. Plus, the phrase “blond fragility” was well worth the price of admission.

Maestro, meanwhile, was impressive in some respects (Bernstein’s exquisitely coiffed hair comes to mind, and articles on Cooper are quick to remind you that he spent six years learning to conduct), but in focusing more on “famous complicated man and also his wife” and less on Bernstein’s music, too often it felt like a movie I’d seen before. This watcher’s take is that Gerwig’s directorial efforts to date have just felt a little fresher, a touch more original, than Cooper’s. (Did you know his A Star Is Born is the fourth time that picture has been made? See also the 1976, 1954, and 1937 versions, plus 1932’s What Price Hollywood? which is basically the same flick.) That said, to date, Gerwig and Cooper share the distinction of having been Oscar-nominated for every picture they’ve helmed. Not a bad place to be.

Those are my thoughts on the Oscars gossip, reader. I’ll have more for you on the other nominees soon, once I’ve caught up on the ones I haven’t seen. For now, I suggest seeking out Past Lives if you haven’t; I don’t think it’ll win anything, but it’s a moving, modern story about loving two people, having ties to two countries, and struggling to reconcile who you are and who you used to be.

OK, in no particular order, here’s what Josh watched…

May December (2023)

What it is:

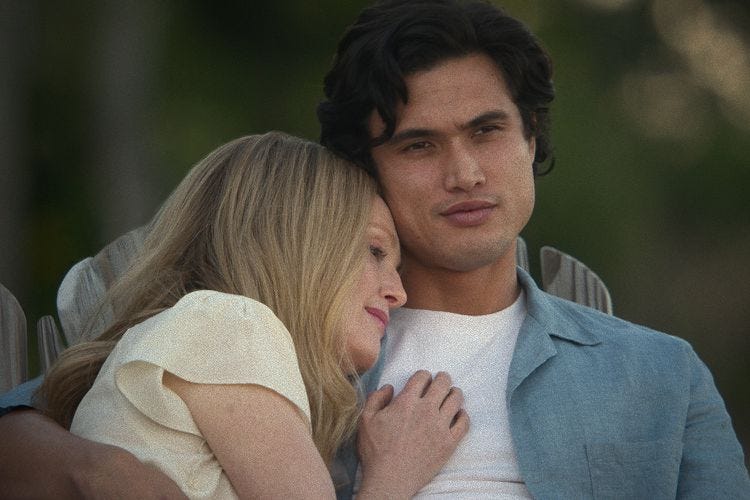

The morally twisty story of an actress, Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), who spends a few days with a woman, Gracie (Julianne Moore), she’s going to portray in a movie. The thing is, the woman is infamous because when she was 36, she was caught having sex with a 13-year-old. She gave birth to their baby in prison; now, 23 years later, they’re married with three kids.

Why I watched it, what I thought:

My ears pricked up when May December was announced, partly for the story (loosely based on Mary Kay Letourneau, a teacher who had sex with her sixth-grade student) and partly because it’s directed by Todd Haynes, who’s made a career out of movies that explore complex psychology. If there’s one director I trust to approach potentially lurid material with a thoughtful eye, it’s him. And the movie — the first written by Samy Burch, whose script grabbed an Oscar nomination — is far less sensationalized than you might expect.

At its core, the flick is about how essentially unknowable other people are, a theme woven throughout the story. Elizabeth arrives at the home of Gracie and her husband, Joe (Charles Melton), having been invited to see the truth behind the tabloid headline. Initially we don’t know who the couple is or what their history contains; the opening minutes dole out information slowly and almost offhandedly, and as the pieces of the past are laid out, what they add up to takes your breath away. The flip side of Elizabeth trying to gain Gracie’s and Joe’s trust, meanwhile, is how much of herself she reveals to get them to open up. It’s a fraught balancing act, if not outright acting: is she being real with them, or just using them to pick up notes for her performance? How will Elizabeth’s movie treat these two people? (As Joe says at one point, the “story” she’s exploring is his life.)

The picture is also about relationships, and the one at its heart throws the story through loops. Gracie and Joe are such a bizarre couple that the movie tingles with unease. You see them trying their best to live regular lives — family dinners, barbecues — in a town where everyone knows their history. At first you, like Elizabeth, are a little fooled into thinking people have moved on. Gracie makes and sells cakes to neighbors, for example, which seems surprisingly normal until you find out who her customers are. Then there are other signals that not all is right, like the package of dog shit someone leaves on their porch. Gracie isn’t too fazed by the latter; she tells Elizabeth it’s happened quite a few times. She also sometimes acts more like a mother to Joe than a wife, counting his beers and telling him to drive Elizabeth home.

As the movie digs into its core relationship, the layers it peels back are endlessly fascinating. On the one hand, Gracie has paid her debt to society, and she and Joe, whatever the circumstances they met in, are legally choosing each other now. On the other, society hasn’t forgiven or forgotten them, and with their kids about to leave for college, it feels like change may be in the air. We see Joe texting with an unknown person and proposing they take a trip together; the person texts back, Aren’t you married? Later he tries to talk to Gracie about their past, but she doesn’t want to revisit it. You’re the one who seduced me, she insists. I was 13, he replies. Yet when Elizabeth points out that he’s still young — he could have another life, Gracie will be fine without him — Joe isn’t sure she will. He seems to sense that leaving Gracie could be good for him but bad for her. (In one scene, Gracie, Joe, and their kids are eating in a restaurant, and in walk Gracie’s ex-husband and they kids they had together — the people she left for Joe. It’s utterly strange and sad.)

Eventually Elizabeth finishes her research and leaves, but just before that something happens that makes her think she’s finally unlocked Gracie. She’s spent days talking to people, probing, asking questions, hearing Gracie be described not as a monster but as a naive person who made bad decisions. Then she talks to Gracie’s son from her previous marriage, and what he tells her makes Elizabeth think, Oh, that’s why she did it. It seems the key to Gracie’s psychology has been revealed. But the movie, like life, is slipperier and more complex than that, and what Elizabeth learns later makes her reconsider whether she knows Gracie at all. That wondering carries over to the ending, when we see Elizabeth shooting a scene for the movie. I won’t tell you what happens, but we realize May December is a hall of mirrors about trying to understand each other and what we do with that understanding once we get it, or don’t.

See it?

Definitely. The complexities of Gracie and Joe’s relationship, and Gracie and Elizabeth’s, yanked me in.

How to watch:

Streaming on Netflix.

Saltburn (2023)

What it is:

If you’re a regular reader of Josh Watched (thanks!), you’ll have heard of this flick by now, and maybe you’ve even seen it; an unexpected number of my friends and frenemies have. If not, Saltburn is — in the imaginings of writer-director Emerald Fennell — a class warfare black comedy with some psychosexual flourishes thrown in. In reality, it’s somewhat less than that.

Why I watched it, what I thought:

I liked Fennell’s previous and first movie, 2020’s Promising Young Woman, well enough. Besides the anticipation of seeing a new flick by a promising young director, I was looking forward to Saltburn for the star turn by its lead, Barry Keoghan. If you’ve seen The Banshees of Inisherin or The Killing of a Sacred Deer or The Green Knight, you’ll know Keoghan is magnetic when playing off-kilter weirdos. In Saltburn he seems to be playing someone much more normal, and therein lies my issue with it. While I don’t think the movie hits most of its marks, there’s one thing it does exceptionally well, something I didn’t really think possible: it makes Keoghan boring.

His character is Oliver Quick, an Oxford scholarship student who befriends a rich classmate and then, over the summer, his family at their country estate. The story has some twists that I don’t want to spoil, but suffice to say Quick isn’t the same person early and late in the movie, and since it’s unclear what he’s up to for a lot of the flick, he struggled mightily to hold my interest. I was reminded of how Alfred Hitchcock, who knew a thing or two about suspense, said the audience needs to know Something Is Going On for suspense to exist. His famous example is two people sitting at a table with a bomb underneath. If we don’t know the bomb is there, we’re surprised when it explodes. But if the camera shows us the bomb, we’re nervously waiting for it to go off.

Since we don’t know Something Is Going On in Saltburn, more has to be going on to keep the story aloft, and not that much is. Quick isn’t a character I particularly cared about, nor the rich sister, nor the Black American family friend (the movie hints at a race angle that it immediately drops), nor even really Felix Catton, the rich heartthrob that Quick may or may not be in love with. (His voiceover narration has much hand-wringing about it.) Most of the people feel like little plot engines. At least Rosamund Pike and Richard Grant, playing the parent Cattons, seem to be having fun; Pike in particular gets most of the best lines. There’s also a boho-ish wreck of a friend (Carey Mulligan again) living with the Cattons who shakes things to life for a few minutes.

A few times the movie does flirt with something electric; if you’ve seen the flick, you know the heavily memed scenes I mean. They feel like empty provocations, though, more than “this makes sense” parts of the plot. Moreover, Saltburn overdoes even these overdoing-it moments, which I can’t help thinking comes down to taste. The movie slurps when it should lick.

Midway through, the story swerves in a way I did like, but it’s hard to know how seriously to take it all, and at times Saltburn wants to be taken quite seriously. But the plot’s machinations feel underhanded and loosely connected. The flick is structured for shock value more than satisfying storytelling, so the emotional through-lines from scene to scene are hazy. As Quick worms his way into the rich family’s good graces, I wasn’t sure whether I was meant to root for him. He’s the socioeconomic underdog, but as a character he’s just kind of there. The younger rich folks keep reminding Oliver he’s a pet, a plaything, this year’s poor friend for Felix. If Saltburn has anything to say beyond that, any particular insight into class, I couldn’t find it. The whole thing just feels sloppy and misconceived.

See it?

I found Saltburn mostly lifeless, but if it’s plastered across the top of your Prime Video page, there are reasons to click play. As Felix, Jacob Elordi is impressively charismatic. Pike is fun to watch, as are Grant and Mulligan. And one scene has the funniest use of an MGMT song I’ve come across in a movie. I’m not recommending the movie as such, mind you. While the credits rolled, I was wondering why Keoghan wanted to be in this and figured it had to be the chance for a lead role, which is perhaps hard to come by when you’re pigeonholed into certain types of characters. Here’s what he said in a recent Variety article about how leading a movie has changed the way people see him:

“It’s nice, man,” Keoghan said. “It’s nice not just being looked at as the weird-looking guy, the unique feckin’ freaky little freak man-child, freak child-man, whatever you want to call it. It’s nice to see people kind of look at you in that way. I’ll be honest. It is nice.” The actor officially declared his “little freak child-man era” over thanks to Saltburn, adding: “And now I’m just Man. Freak-Man. Man-Freak.”

Hard to argue with that. Anyway, if you see Saltburn, let’s chat — it’s more fun to talk about, and make fun of, when you don’t have to play coy.

How to watch:

Streaming on Amazon Prime.

Ghost in the Shell (2017)

What it is:

The platonic ideal of a shallow Hollywood remake. In this case, it’s a live-action version of one of the greatest animated movies ever made, 1995’s stone-cold anime classic of cybernetic technology, cyberpunk influences, and philosophizing about identity in a digital world.

Why I watched it, what I thought:

Ghost in the Shell, the original, is fantastic. It follows Major Motoko Kusanagi, a sort of cyber-enhanced SWAT team leader, as she and her partner investigate a mystery that sprawls across technological and philosophical realms. It’s near-future Japan, and implants let people connect their brains to computer networks, as well as swap out their body parts for mechanical upgrades. Major (that’s what everyone calls her) and her partner work to hunt down the Puppet Master, an entity that can control people by hacking into their brains, turning them into assassins or just temporary criminal goons. Into the story come artificial intelligence, technological sentience, and questions about what it means to have a soul; if you’re more machine than flesh, what are you? (One of those questions that I particularly enjoy is whether an AI could ask for political asylum.) The soundtrack is great and the action scenes hold up well. If you’re wondering why this all sounds a little familiar, it’s because the picture was a major influence on The Matrix.

Ghost in the Shell, the remake, is something else. It’s such a perfect embodiment of bad remake stereotypes that I wondered if the movie was putting me on. The nuance and thoughtfulness of the original are nowhere to be seen; ditto most of the themes worth thinking about. On a line-by-line basis, the characters are so glaringly obvious about what’s happening and how they feel about it that the movie never once threatens to deepen into something meaningful. Reader, it’s like the studio put the original script through free translation software. It’s like they tasked a robot to write the new flick — but a robot that wasn’t programmed to write. It’s hard to believe anyone read this script and thought, Yes, this is how normal people talk. This movie will be good.

Another thing with the remake is Scarlett Johansson’s casting as Major. In other words, a white woman plays a Japanese character, which more than a few commenters were not pleased by. (Others said it’s beside the point what someone’s body looks like in a cybernetic future, or in an American flick.) The movie tries to skirt the issue by making Major white, but weirdly circles back to it in a way you have to see to believe. That plotline seems like an attempted homage to the original flick, but, like everything else here, just feels off. I appreciate Johansson’s willingness to tackle roles that investigate her looks and body — 2013’s Under the Skin is far superior — but most of her performance is the wig she wears for Major’s trademark look. She’s…it would be on the nose to say robotic, but wooden, maybe? I’ve seen ScarJo act well before, so I can only assume her badness is due to the lethal combination of this script and this director. Still, she’s nearly matched by Juliette Binoche, one of the best actresses in the world, who’s laughable as the scientist designer of cybernetic bodies. The scenes where she has terse conversations with ScarJo’s taciturn cyborg are among the worst — but they do have competition.

See it?

If you’re looking for a good movie, skip it. But if you’re interested in sci-fi or adaptations (especially U.S. remakes), I’d carve out a few hours and watch both versions of Ghost in the Shell as a double feature. Or, perhaps more realistically, just watch the first one. I can’t imagine this movie existing as anything other than a giant screaming billboard for the original.

How to watch:

Streaming on lots of sites.

And that’s it for this edition of Josh Watched! Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more updates on which Oscar nominees you need to bother caring about.

See you next month!